Have you been diagnosed with a skull base tumour?

Hearing that you have been diagnosed with a brain tumour can obviously come as a huge shock, however, treatments for brain tumours have seriously moved on and the latest therapeutic modalities are now highly effective. In particular, a non-invasive treatment known as Gamma Knife quite literally offers a new major 'ray of hope'.

What are vestibular schwannoma and meningioma skull base tumours?

Vestibular schwannoma and meningioma are types of benign skull base brain tumours that grow in and around the brain. They have similar behaviour and treatment options. They particularly grow in the region of the cranium known as the ‘skull base’, where critical blood vessels and nerves can lie. Their management is complex, and based on key core principles that guide decision making.

Meningiomas - benign tumours that grow from the lining of the brain

Meningiomas - benign tumours that grow from the lining of the brain

Meningiomas grow from the lining of the brain known as the ‘meninges’. They grow slowly, usually around 1-2 mm a year, and they do not spread to other parts of the body. However, depending on where they grow they can start to cause symptoms by pressing on the normal structures of the brain. In regions of the brain where there aren’t many important functions, they can grow very large before showing symptoms and being diagnosed. This is particularly so for tumours pressing on the frontal lobes of the brain, which cause more subtle problems such as personality changes or headaches. When located further back and on the skull base, a tumour can cause as range of symptoms.

What are the symptoms of brain tumour?

- weakness,

- numbness,

- vision loss,

- double vision

- problems with balance.

A subgroup of these tumours can sometimes be diagnosed incidentally when scans are performed for other reasons.

The ideal form of imaging for an accurate diagnosis is an MRI of the head with contrast medium. This will show the characteristics of the tumour, and its relationship with the surrounding brain structures. Once a diagnosis is made, a treatment plan can then start to be formulated.

Swelling or oedema caused by skull base tumour

In some cases the scan may reveal that the tumour is causing swelling in parts of the brain and this is called ‘oedema’. This oedema can cause symptoms in addition to those that result purely from the pressure of the tumour itself. If the oedema is significant and causing symptoms, treatment with steroid medication, such as ‘dexamethasone’ may be needed for a period of time. However, because long term use of steroids is associated with medical complications such as weight gain and osteoporosis, their use is usually restricted to short periods.

Treatment options for meningiomas

Treatment options for meningiomas

There are three main options for treating meningiomas. These are:

1) conservative management with ongoing imaging,

2) radiation treatments including Gamma Knife, and

3) surgical removal or reduction known as ‘debulking’.

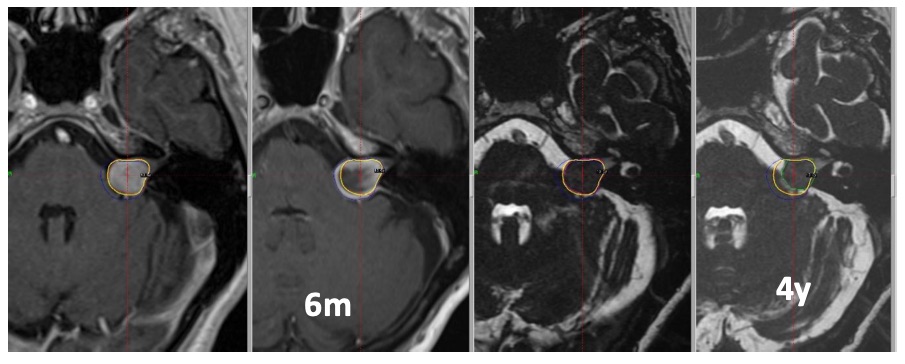

The majority of tumours can be observed in the first instance with surveillance imaging. This period is important to determine the behaviour of the tumour and a six monthly MRI scan is often appropriate. If new symptoms do develop in the meantime then the MRI scan can be brought forward. The observational period also allows time to fully characterise the tumour diagnosis so that the most appropriate treatment options can be considered. In these circumstances, if growth is demonstrated at six months, a clear and quick decision on the best form of treatment can be made.

Treating large tumours

For large tumours, especially those causing significant pressure on the brain resulting in symptoms, surgical removal performed by a highly experienced team is the preferred treatment. Depending on the location and critical structures involved, this may be total or partial removal. With a total excision, the chance of recurrence in the future is extremely low. The pressure on the brain should be relieved with the prevention of further symptoms, and there is often improvement in existing symptoms. This improvement in symptoms may take place over a period of months as the swelling gradually settles with time. If there is any residual tumour, this is checked with serial imaging, and any further growth then typically treated with radiation therapies.

For large tumours, especially those causing significant pressure on the brain resulting in symptoms, surgical removal performed by a highly experienced team is the preferred treatment. Depending on the location and critical structures involved, this may be total or partial removal. With a total excision, the chance of recurrence in the future is extremely low. The pressure on the brain should be relieved with the prevention of further symptoms, and there is often improvement in existing symptoms. This improvement in symptoms may take place over a period of months as the swelling gradually settles with time. If there is any residual tumour, this is checked with serial imaging, and any further growth then typically treated with radiation therapies.

Types of radiation therapy for skull base tumours

Stereotactic radiosurgery

Radiation can be delivered in different forms. The most focussed and targeted is termed ‘stereotactic radiosurgery’. For well circumscribed, deep seated tumours, this is the best option as this form of treatment can target a high dose of radiation to the tumour, whilst minimising any spread to the "normal" brain.

Gamma knife radiosurgery - non-invasive surgery

The most common form of stereotactic radiosurgery is called ‘Gamma knife radiosurgery’. This technique achieves the highest level of accuracy by using a stereotactic frame that is fitted to the head during the treatment. The other advantage of radiosurgery is that it is non-invasive, and so in some circumstances avoids the need for open surgery.

It is convenient and performed as a day case. However, it does have some limitations and cannot be used to remove a tumour that is already causing symptoms. The aim is to arrest growth. As a general rule of thumb, a tumour that is less than 3cm in size can be considered for radiosurgery. Smaller is better for this treatment type, as larger tumours can be susceptible to swelling reactions in the brain. Larger or more diffuse tumours may be treated using a process of ‘fractionation’ where radiation is delivered on multiple occasions at smaller doses.

Vestibular Schwannoma and hearing tests

A vestibular schwannoma is also a slowly growing benign tumour that grows around the base of the skull. It grows on the hearing and balance nerve, and so most commonly presents with hearing loss or tinnitus on one side. It can also cause balance problems. As they grow larger these tumours can press on the nerve that gives sensation to the face resulting in facial numbness, or shooting pains in some circumstances. If you do have hearing loss on one side, the first port of call is an audiologist who will be able to tell if this is the kind of problem that can be associated with such tumours (and requiring an MRI scan), or is due to another reason such as impacted ear wax for example. An MRI of the area known as the internal auditory meati (IAMs) is the diagnostic scan of choice if the audiology test suggests an atypical hearing loss requiring further investigation.

Location of tumour dictates treatment choice

These tumours grow approximately 1 to 2 mm a year, and are also primarily treated with either surgical removal or focussed radiation treatments. The location of these tumours significantly affects the decision on what treatment is best. They grow in a confined space between the hearing structures of the ear and the brainstem, called the cerebellopontine angle. There is very little space here to accommodate tumour growth or swelling, and there are many critical nerves and blood vessels. The brainstem itself is densely packed with fundamental neural structures. In this context, the management of these tumours should be guided by an experienced multidisciplinary team with the ability to provide all types of treatment to a very high level.

The main difficulty with treating vestibular schwannoma is the proximity of the nerve to the face on that side. This ‘facial nerve’ is immediately adjacent to the hearing and balance nerve, and as such becomes progressively stretched by tumour growth. Because this stretching happens slowly, the nerve is rarely impacted by this, and in fact can be flattened very significantly by the tumour without any loss of function. However, because it is compressed it is susceptible to injury from treatments for the tumour resulting in facial weakness or complete paralysis in some circumstances.

In the first instance, it is usual practice to monitor the tumour and assess its behaviour with a repeat scan within 6 months. A significant proportion of tumours, particularly those of a smaller size, do not grow, and these may be followed up long term with an MRI scan once a year. If the tumour is stable for a number of years, this MRI scan frequency can be increased over time. If the tumour grows then intervention is usually recommended.

The majority of smaller, growing tumours are suitable for treatment with stereotactic radiosurgery techniques such as gamma knife radiosurgery

The majority of smaller, growing tumours are suitable for treatment with stereotactic radiosurgery techniques such as gamma knife radiosurgery. This has the following benefits:

- of being non-invasive compared with open surgery, and

- has a lower risk of injury to the facial nerve in the region of 1% of cases or less.

It does not remove the tumour, but it prevents further growth in approximately 95% of tumours or more depending on the size. There are risks of exacerbating balance problems for example for a period of time, or accelerating hearing loss, but compared with ongoing tumour growth these side effects are usually well tolerated. Treatment is carried out as a day case, and normal activities including work can continue within a few days.

Treating large Vestibular Schwannoma tumours

Large tumours causing swelling in the "normal" brain usually require surgical intervention. At very large sizes, up to 4cm for example, the tumour may prevent the normal brain fluid exiting the brain, which is called ‘hydrocephalus’. When this happens a ventriculoperitoneal shunt can be inserted which bypasses this obstruction and carries this cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain to the abdomen where it is absorbed.

For tumours above 2.5cm, surgery is usually considered in order to remove as much tumour as possible and relieve the pressure on the brain. Such surgery is usually performed in specialist centres with sufficient expertise in the management of such tumours. Due to the technical demands, these operations are usually performed collaboratively with both ENT and Neurosurgery skull base surgeons.

Translabarynthine or retrosigmoid approach

Depending on the configuration of the tumour and surrounding structures, this may be most commonly performed via a ‘translabyrinthine’ approach, which traverses the hearing and balance structures of the ear, or a ‘retrosigmoid’ approach performed alongside the brain’s balance organ, the ‘cerebellum’. There is also the option of ‘middle fossa’ approaches in selected circumstances.

... avoiding the facial nerve

The crucial aspect of surgery is to safely remove enough tumour without damaging normal structures such as the facial nerve. During surgery this nerve is monitored with electrophysiology to ensure it is functioning normally. It is usual practice to perform ‘facial nerve sparing’ surgery, where a portion of tumour is deliberately left behind on the nerve to preserve its function. If this residual tumour grows subsequently, it can then be safely treated with radiosurgery or radiotherapy at a low dose in the future.

Gamma Knife radio surgery prevents further growth in 95% of tumours

The majority of tumours, particularly those of a smaller size, are suitable for treatment with stereotactic radiosurgery techniques such as Gamma Knife radiosurgery. This has the benefit of being non-invasive compared with open surgery, and has a lower risk of injury to the facial nerve - in the region of 1% of cases or less. It does not remove the tumour, but it prevents further growth in approximately 95% of tumours or more depending on the size. There are risks of exacerbating balance problems for example for a period of time, or accelerating hearing loss, but compared with ongoing tumour growth these side effects are usually well tolerated. Treatment is carried out as a day case, and normal activities including work can continue within a few days.

Summary

In summary, the treatment of skull base tumours such as meningiomas and vestibular schwannomas is complex with many parallels between the two. Each patient and tumour should be assessed individually, and the range of possible treatment options presented to allow an informed decision to be made for the particular circumstances. It’s important to see an experienced multidisciplinary team that can provide all the available options so that treatment can be tailored appropriately.