The importance of facial appearance cannot be understated. Ayone who has suffered facial scarring as the result of trauma or surgery knows exactly just how important facial reconstruction is. Equally important for anyone considering facial reconstruction and wishing to be involved in the medical discussion - is a knowledge of the fundamental general principles that are central to the approach that your surgeon will adopt.

Starting with, "return what is normal to the normal position and retain it there".

Contents

General Principles of Facial Reconstruction Surgery

Our faces play a pivotal role in our daily social interactions, through expression of emotions, appearance and most importantly identity. The face is our carte visite, the place where our individuality and our personality is manifested. It is understandable then that permanent scarring of the face caused by severe trauma or surgery can be profoundly damaging for the person affected. For this reason facial reconstruction is extremely important and there are a number of fundamental general principles that underpin the surgical techniques employed.

The Development of Facial Surgical Reconstruction

The first attempts at facial reconstruction took place several hundred years ago and are attributed to one of the forefathers of modern reconstructive surgery, the genius Gaspare Tagliacozzi. Tagliacozzi was Professor of Anatomy at the Medical School of Bologna in Italy in the late 16th century. He is credited with being the first surgeon to attempt reconstruction of the nose by using a flap of skin taken from the forearm. The flap, called a pedicle, was attached to the nose and the patient's arm was bandaged in a raised position until the skin of the arm had attached itself to the nose. The pedicle was then cut from the arm and the attached skin could then be shaped so that it resembled the nose.

This in effect corresponds to a method that was later called "Robin Hood's tissue apportionment", where tissue from an area of abundance is used to make up for tissue deficiencies in another part of the body. This was achieved by using "advancement" or "rotational" flaps. The full development of this notion gave birth to modern ideas of "transfer" of flaps from other areas of the body and ultimately "transplantation" of flaps. The former requires the employment of "micro-vascular" techniques that involve the "transfer" of tissue together with their supporting arteries and veins, which then have to be connected to the recipient vessels in the neck.

Close collaboration with immunological manipulation techniques is also necessary as part of anti-rejection treatment of the "transplant". The reported success stories of total face transplants ultimately signify how advanced reconstructive surgery has become. However, surgical success would not be possible without close interaction between various medical disciplines including immunology, intensive care and post-surgery neurological and psychological rehabilitation.

Replacing Tissue Loss in Kind

What this means in practice is that bone should be replaced with bone, muscle with muscle and skin with skin. Nevertheless, the 3-dimensional complexity of the anatomy of facial structures, including a multitude of small muscles attached to thin, sometimes hollow bones of irregular, complex shape makes such a principle difficult to apply successfully.

In particular, "transitional" areas between dry skin and moist mucosa, such as at the junction of the outer lip to vermillion border and inner lip and the junction of thin eyelid skin to the tarsal plate and the conjunctiva of the eye make reconstructive planning a daunting surgical task.

Returning to Normal

For the reason set out above, the further principle of "return what is normal to the normal position and retain it there" is of paramount importance. Displacement, or loss of structures, can occur as a direct result of trauma or planned surgical excision or even scar contraction. The surgical correction needs to take into account the normal appearance or in cases of long established deficit the aesthetic projection of what normal would have been for the missing facial structure.

Reconstruction by unit

This leads me to the next principle, which is "reconstruct by units".

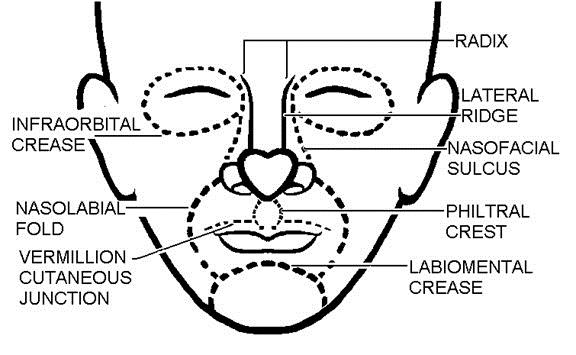

This diagram* demonstrates how the face can be divided into "unit borders" that are demarcated by natural folds, creases and generally "transitional" anatomical areas. Respecting the boundaries of these "aesthetic units" during surgical procedures gives a more "natural" expression to the reconstructed area, concealing the differences in texture, thickness, composition, colour and light reflection between the native and the reconstructed tissues.

In addition, this breaking down of the face into aesthetic units provides the surgeon with an operative "road map" of the exact reconstructive needs caused by the defect. In this way, a complex 3-dimensional defect involving various anatomical borders can be divided into smaller anatomical units, which can then be considered almost independently during the planning of the surgical procedure.

Importance of function over form

The functions of the face can be grouped into physiological, expressive and aesthetic. The face also plays a very important role in the patient's identity.

The physiological functions of the face include the crucial anatomical barrier that the skin of the face provides between the internal and external environments and the abundance of sensory cutaneous nerves that can be seen as the primary sensory organ of the body. The mouth forms part of the alimentary tract; and the nose (and secondarily mouth), the respiratory tract, whilst also hosting the olfactory nerve endings that provide the all- important sense of smell.

Finally the external parts of the eyelids protect the orbital globes from mechanical injury while the internal side together with the conjunctiva provides a pliable, thin layer protecting the cornea of the globe.

The expressive function of the face is underscored by its importance as the main instrument of non-verbal communication, allowing us to express and communicate our thoughts and feelings. Finally, the aesthetic function of the face allows social acceptance and integration.

Invisible Scars

The quest of modern facial reconstructive surgery techniques then is to provide, as far as possible, "invisible scars" in the face, which means concealing outside the most visible anatomical areas. Fortunately the face does offer such an opportunity. There is a vast array of operations that can be performed through the oral cavity including surgical procedures for the bones of the mid- and lower third of the face and their overlying soft tissues.

Equally, surgery around the orbital globes can be performed through the conjunctiva, allowing access to the eye socket and the supportive bone with no need for skin incisions. Finally, the combination of facial incisions in conjunction with concealing incisions behind the ears or within the hairline can provide almost seamless, invisible access to the entire surface of the face and the facial skeleton. This allows not only cosmetic improvement of facial features, but primarily serves the ongoing need for social integration by minimising defects and scars and subsequently by minimising the indelible traces of previous illnesses.

References:

* Facial anatomy in cutaneous surgery (Ida Orengo and Vivek Iyengar - Medscape March 28, 2013)

Associated with the nervous system and the brain.

Full medical glossary