This article discusses community acquired pneumonia, a serious illness that is responsible for almost 10% of all chest infections in the UK. This will be helpful to anyone suffering from the symptoms of pneumonia who would like to know how they can be diagnosed and how to seek treatment.

Contents

How prevalent is pneumonia?

Pneumonia has been recognised as a significant illness for many centuries. Indeed, it was the ancient Greek Hippocrates, who first described what he could hear on listening to the chest of a person suffering from pneumonia! Prior to the antibiotic-era, which began with sulphonamide antibiotics in 1938 and then penicillin in 1944, popular treatments included blood-letting, leeches, emetics to encourage vomiting and enemas. Recognition that the illness was caused by bacteria did not occur until the late 1800’s with the identification of Friedlander’s bacillus. In actual fact, most of the bacteria he identified were pneumococcus, which we now recognise to be the most common cause of pneumonia.

Even in the modern antibiotic-era pneumonia is a significant illness. Despite antibiotics, pneumonia can be fatal, even in previously healthy individuals. However, to put this in context, there are around 1.5 million episodes of chest infections in the community each year in England and Wales, of which only around 5–10% are pneumonia. Around 3,000 of these cases will prove fatal but more than 80% will succumb to “bronchopneumonia”, commonly a terminal event in people with serious underlying medical conditions. Overall men are affected twice as often as women.

Pneumonia is often classified as “community acquired” if it occurs in the community; hospital-acquired pneumonia is a pneumonia that develops three days or later into a hospital admission, and is the third most common hospital acquired infection. This article discusses community acquired pneumonia.

Symptoms of pneumonia

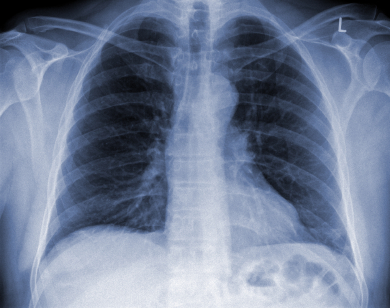

People with pneumonia have a productive cough, usually coughing up purulent (coloured) phlegm or sputum. Occasionally the cough can be more dry than productive. In a minority of cases the sputum may be tinged with blood and occasionally fresh blood clots may be coughed up; these usually settle with treatment. Some people experience chest pains (because of, or worsened by, coughing), and breathlessness (associated with coughing spasms, or all the time). Chest pains that are worse on breathing in may be due to extension of the pneumonia to the surface of the lung (the outside lining or visceral pleura). The pleural surface becomes inflamed and roughened as does the opposing pleural surface (parietal pleura lining the inside the chest cavity). The two roughened surfaces rub together with each breath and cause the pain called pleurisy. This can lead to accumulation of a small amount of fluid in the pleural space (visible on a chest x-ray).

There can also be constitutional symptoms that can occur with any infection such as fever, chills, shakes and rigors, loss of appetite, muscle aches and pains and headache. An upper respiratory infection (“cold”) due to a respiratory virus or Mycoplasma infection may precede the pneumonia. Acute confusion is more likely in severe pneumonia; it is also more common in the elderly. Certain bacteria that can cause pneumonia also produce symptoms outside the chest, most commonly skin rashes.

Most people have symptoms for around a week although those with Pneumococcus or Staphylococcus may become very unwell in a matter of hours.

When examined, fever is often present, but may be minimal or absent in the elderly and the seriously ill. Cold sores may also be present. On listening to the chest the breathing sounds may be louder, a term known as bronchial breathing. More commonly “crackles” are heard. If there is a significant fluid collection in the pleural space tapping over the affected area may sound “stony dull” with no breath sounds heard at all with the stethoscope.

In lower lobe pneumonia, there may be abdominal pain and tenderness in the abdomen adjacent to the affected lobe.

Diagnosing pneumonia

None of the symptoms or clinical signs can definitively pinpoint the responsible bacterium, or reliably differentiate between a chest infection and pneumonia. A diagnosis of pneumonia can only be made when typical changes are seen on a chest x-ray in the presence of a compatible medical history. The chest x-ray may also demonstrate fluid collecting in the pleural space, and its size. Conversely in the absence of any changes on a chest x-ray the diagnosis is “chest infection”.

Therefore, a definitive diagnosis requires a compatible medical history together with examination findings, and a chest x-ray for confirmation. The choice of what investigations are required is often determined by how unwell the person is. In milder pneumonia no investigations at all may be needed before antibiotic treatment can be initiated. As long as the patient responds to treatment no further investigations are needed. Where there is doubt a chest x-ray can confirm the clinical suspicion of pneumonia. A follow up chest x-ray is recommended to confirm clearance, and to identify any underlying lung disease.

In the more unwell person rapid urine and blood tests can identify Pneumococcus and Legionella. Microbiology tests on the blood (blood cultures) should always be done as the infection may be in the bloodstream intermittently. Sputum may be sent for culture, particularly in people with underlying lung disease. In milder pneumonia a sputum sample is not necessary and the result is unlikely to change treatment. If there is any significant pleural fluid collection a sample should always be sent to make sure that it too is not infected. If the person is hospitalised and is unable to provide a sputum sample it is sometimes necessary to obtain one by a more invasive method such as bronchoscopy. After mild sedation a fine fibre optic tube with a camera is used to get samples from the affected area of lung; this has the advantage as results are not contaminated by secretions from the upper airway and are more likely to be representative of the infecting organism.

Most pneumonia is caused by bacteria, but on occasion it can be due to viruses. The diagnosis of viral and some atypical pneumonias can usually only be done by doing paired blood samples two weeks apart. The test relies on the body’s immune system mounting an immune response to the organism causing at least a four-fold rise in antibody numbers. A raised but persistent titre suggests infection sometime in the past. Some viruses can be only be identified by more sophisticated diagnostic tests (such as polymerase chain reaction from nasopharyngeal swabs) and these are usually only requested in seriously ill people in hospital, particularly those in intensive care.

Identifying the sickest patients

There are a number of scoring systems available that can help to determine who is safe to be treated at home and who would require treatment in hospital. Those needing treatment in hospital are usually at greater risk of complications and/or dying of the pneumonia. Those who are most unwell and need closer supervision will be treated in a medical High Dependency Unit, or on the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Rarely the pneumonia is so severe that breathing is difficult even with supplemental oxygen and a period of intensive ventilator support on the ICU is necessary. Sadly despite modern antibiotics and full supportive care on ICU some people still die of pneumonia.

How is pneumonia treated?

The mainstay of treatment for bacterial pneumonia is antibiotics. What antibiotics and where they are administered is dependent on how unwell the person is. In most people with uncomplicated pneumonia a single antibiotic such as amoxicillin can be given and the person treated at home. There may be other reasons (e.g. other significant health problems) that mean the person needs to be treated in hospital. Those who score highest should be treated in hospital with two antibiotics (usually amoxicillin and a macrolide antibiotic such as clarithromycin, unless penicillin allergic). People who are truly penicillin allergic are given a quinolone antibiotic (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin). In most cases 7–10 days of antibiotics is sufficient, although some may take longer to get better (the elderly or those with immune suppression). In those who are unable to tolerate oral antibiotics the treatment should be given intravenously in hospital.

Failure to improve in response to antibiotics should prompt a review of treatment. This should include reviewing the diagnosis (is it really pneumonia?), the organism (are the antibiotics being targeted against the right bacterium?), the duration of treatment, development of complications and potential “host factors” (e.g. age, drugs, other problems such as diabetes, immune suppression) that delay response.

The review of treatment may involve repeat blood tests, a chest x-ray, a sputum sample and a sample of pleural fluid if necessary. If the person is unwell, the fever fails to settle or they develop complications they should be reviewed by a respiratory specialist who may request further investigations and /or treatment.

Although it is still possible to die from pneumonia, in most cases with prompt diagnosis and treatment recovery is uncomplicated and complete. It is recommended that a follow up chest x-ray is done around six weeks later, particularly in smokers and those over the age of 50 to check for complete resolution and to make sure there is no underlying lung abnormality such as lung cancer.

Repeated episodes of pneumonia (and possibly infections elsewhere) should trigger further assessment; this may be a clue to an underlying immune defect impairing the ability to fight infections, or to rare inherited conditions predisposing to chest infections (cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia) or to abnormal underlying lung (bronchiectasis). Opinion from a respiratory specialist should be sought.

Finally, all patients admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia and aged over 65 should be offered pneumococcal vaccination in line with Department of Health guidelines. All patients who smoke should be offered support to stop smoking.