This article discusses the diagnosis and treatment of voice disorders. Problems with the voice can range from laryngitis requiring simple medical management to more complicated disorders needing surgery.

Contents

- Introduction

- Definition of voice disorder

- Classification of voice disorders

- Evaluation

- Management of voice disorders

- Conclusion

Introduction

The word ‘voice’ refers to the production of sound of a given quality, whereas speech refers to the shaping of sounds into intelligible words. Voice quality is the continuous background to speech production, which involves a complex physiological (functional) and anatomical (structural) system. Voice disorders represent communication dysfunctions; a large population of people estimated between 3 – 10% of the general population are affected by these.

Individuals with voice disorders range from a simple case of laryngitis that usually resolves spontaneously to more sinister physical or organic conditions such as laryngeal malignancy. The main symptom in people with voice disorders is hoarseness or dysphonia, which describes an alteration in voice quality.

Definition of voice disorder

It is difficult to define a normal or abnormal voice quality. Dr Aronson, Speech and Language Pathologist from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA defined it as ‘a voice disorder exists when quality, pitch, loudness or flexibility differs from the voices of others of similar age, sex and cultural group’. A voice disorder may also exist when the structure of the laryngeal mechanism, the function, or both no longer meet the voicing requirements of the speaker. In medical practice, hoarseness is described as a symptom of laryngeal disorder, which is often the first and only signal of disease, local or systemic, involving this area.

Classification of voice disorders

Voice disorders can be classified as organic and non-organic; the latter are often referred to as functional or psychogenic types. In organic voice disorders, the faulty voice is caused by structural or physical disease of the larynx itself, or by systemic illness that alters the laryngeal structure. Organic disorders of vocal mechanisms that may result in voice problems tend to arise from the more superficial structures of the vocal fold, the epithelium (lining) and the superficial layer of the lamina propria (the layer of the vocal fold just below the lining). Those arising from the lining include white patches (keratosis, leukoplakia), wart like growths (papillomas) and sinister ones (carcinoma). Voice problems associated with systemic illnesses i.e. that of the nervous system involvement include myasthenia gravis (weakening and tiring of muscles) and vocal cord paralysis. Voice changes are also seen in some patients with tremors (Parkinsonism) and hypothyroidism. Changes of the environment outside the larynx for example, due to acid reflux or a post nasal drip due to sinusitis can irritate the laryngeal lining and cause hoarseness.

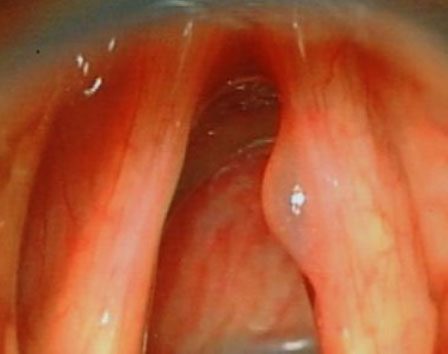

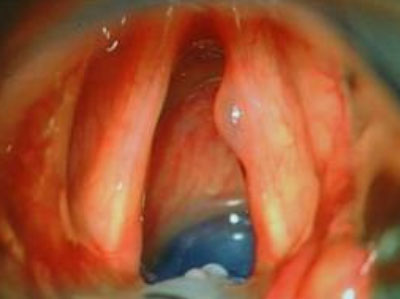

Functional or non-organic voice disorders are non-physical in origin or result from faulty habits of voice use. The voice sounds abnormal despite normal laryngeal anatomy and physiology. Non-organic disorders can be divided into habitual vocal problems, secondary to vocal misuse/abuse, and psychogenic vocal problems. Habitual dysphonias can alter the delicate laryngeal lining from prolonged misuse/overuse. These include nodules (Fig. 1), polyps, cysts (Fig. 2), oedema, ventricular dysphonia, laryngitis and contact ulcer. Vocal cord nodules and polyps usually arise from trauma and changes in the basement membrane zone of the epithelium. Cysts and Reinke's oedema mainly involve the superficial layer of the lamina propria.

Psychogenic voice disorders include musculoskeletal tension disorders and conversion voice disorders: muteness, aphonia and dysphonia which can be traced to the anxiety or depression produced by life stress, psychoneuroses or personality disorders.

Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation

This includes a thorough history taking and physical, laryngeal and perceptual evaluation. The primary objective of the diagnostic voice evaluation is to discover the causes of the voice disorder, and to describe the nature of the vocal symptoms in order to assist the laryngologist and the voice team in making a differential diagnosis and recommending appropriate treatment. The differential diagnosis begins with categorising the abnormal voice on the basis of laryngological, physiological and neurological evidence.

Physical evaluation

Voice evaluation includes a history of the voice disorder, including details of previous voice problems, the onset and the current disorder and its course, as well as events associated with the onset. Information is obtained on the patient’s lifestyle, health, social history, and occupation and stress factors. The occupation of the patient determines the level of voice usage. The laryngologist carries out a comprehensive otolaryngological (ENT) examination. This includes neck examination, laryngeal palpation and examination.

Laryngeal evaluation

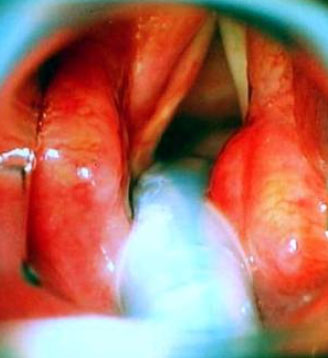

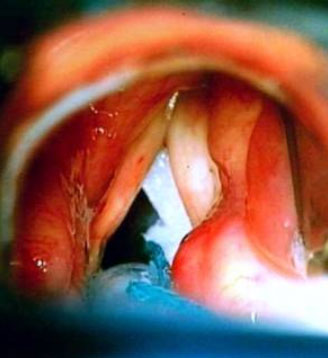

Advances in technology have resulted in improved accuracy and objectivity, and information about the action of the vocal cords can be obtained without the need for invasive procedures. Techniques such as video strobo-laryngoscopy (Fig. 3) which involves video recording the laryngeal movements with special stroboscopic light can provide accessible information and documentation to the patient and health professionals. Rigid and flexible laryngoscopic assessment with stroboscopic light helps in documentation of the laryngeal anatomy; any asymmetry and changes in vocal cord movements are recorded.

The attention to detail helps in diagnosing lesions which can be often missed with cursory and mirror laryngoscopy like small subepithelial cysts and sulci.

Perceptual evaluation

The acoustic analysis of voice production permits a quantitative analysis of the multidimensional physical characteristics of the voice signal and an inference about the underlying physiological mechanism. Acoustic characteristics of the normal voice are age and sex-dependent; they are analysed during sustained phonation tasks and during continuous speech. Simultaneous acoustic, laryngoscopic or electro-laryngographic measures may be used to confirm the nature of phonatory events. Electro-laryngography which analyses vocal cord vibrations by measuring electrical activity of the larynx gives information about the action of the vocal cords by using non invasive procedures.

Quality of life measures in the form of questionnaires have become increasingly important in evaluation of the voice patient, and of the efficacy of treatment.

Radiological and haematological investigations

All patients with voice disorders require objective assessment and measurement of vocal function as discussed above. In addition radiological tests are helpful in the diagnosis of voice disorders. Traditional x-rays are replaced by CT and MRI scans, some offering 3D reconstructed images of the larynx and virtual ‘endoscopy’. Specific haematological tests such as thyroid function tests are also useful where hypothyroidism is suspected.

Management of voice disorders

There are three general approaches to the management of voice problems: medical, surgical, and behavioural including speech therapy. It is often the case however, that optimal treatment requires the use of a combination of treatment types. Surgical management (phonosurgery) is considered the more radical form of intervention aimed at improving voice quality.

Medical management

The medical approach to the treatment of voice disorders refers to non-invasive techniques which do not involve surgical removal, reconstruction or alteration of tissue. Acute laryngeal problems in which the vocal cords demonstrate redness, swelling or irritation (for example those resulting from gastro-oesophageal reflux and allergy) will be medically treated. Proton pump inhibitors used to control and treat acid reflux play an important role.

Surgical management (phonosurgery)

Surgical management of voice problems can be differentiated into techniques that are broadly related to hyperfunction or hypofunction of the larynx. Hyperfunction of the larynx results in discrete pathology which is as a result of increased activity e.g. vocal nodules at the point of maximal contact between the two vocal cords. A thorough understanding of the structured micro-anatomy of the true vocal cord is implicit to effective management. Hypofunction of the larynx occurs where the laryngeal function on one or both sides may be compromised, e.g. a paralysis of one side resulting in air escape as the two vocal cords do not meet in the midline and result in glottal incompetence (air leak) and a weak voice.

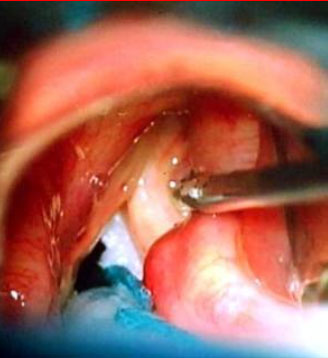

Hyperfunctional or discrete benign pathology is surgically managed by surgical removal of affected tissue with minimal to no resection of uninvolved structures. Many of these lesions, with the exception of nodules and some polyps arise from the superficial layer of the lamina propria, with relative sparing of the epithelium and basement membrane zone. Surgical exposure is through a small incision immediately adjacent to the affected tissue: this permits dissection and removal of the lesion with minimal disruption of overlying epithelium or surrounding superficial layer of the lamina propria. Every effort is made to avoid disruption of the underlying vocal ligament. The dissection is precise respecting the medial vibrating cord of the vocal cords to ensure optimal vocal function postoperatively (Figs. 4–6).

There is some controversy regarding excision of nodules and polyps. Some authors espouse a sub-epithelial approach to excision while others recommend direct excision including the epithelium, but resection to be limited to the lesion with limited to no excision of underlying superficial layer of lamina propria.

There is also controversy relating to the method of removal of these latter lesions with some authors recommending use of ‘cold steel’ and others preferring use of a microspot CO2 laser. The crucial issue is to cause as little damage as possible to the underlying structures. I prefer cold steel instruments, this does not result in collateral thermal damage and the specimen can be analysed histologically for a tissue diagnosis.

Surgery for hypofunctional disorders usually encompasses surgery for glottal incompetence where the two vocal cords are unable to approximate in the midline which is a requirement for normal phonation. This includes, a wide group of conditions affecting symmetrical movement and mobility as caused by paralysis, paresis, arytenoid dislocation/fixation, atrophy, and areas of adynamism or insufficiency as caused by vocal scar, vergeture or sulcus vocalis. The aim is to create a smooth, pliant platform against which the other vocal cord can optimally vibrate and which will allow for generation of a symmetrical mucosal wave.

Two main surgical approaches are used (a) external – laryngeal framework surgery and (b) endolaryngeal; each of value in differing clinical scenarios. Laryngeal framework surgery involves manipulation of the tension and position of the vocal cord through changes in the framework of the larynx. In endolaryngeal approaches changes of bulk and position of the vocal cord through endolaryngeal manipulation is achieved with insertion of fillers, and/or development of local flaps of mucosa.

The surgical management can be carried out under local or general anaesthesia. Local anaesthesia for external approaches involves injecting around the neck crease incision and underlying soft tissue. Although the patient is mildly sedated, the advantage of local anaesthetic procedure is the ability to fine tune the voice in an awake patient. General anaesthesia (GA) is offered where the procedure is planned to last longer and majority of endolaryngeal procedures are carried out under GA.

External approach

External approaches to treating voice disorders were championed by Professor N Isshiki from Kyoto, Japan who pioneered laryngeal framework surgery in the 1980s. These approaches have more recently been refined by many surgeons. Silastic, Gore-Tex, hydroxyapatite, titanium and many other materials have been used as implants; the key issue is bringing the affected vocal fold towards the midline – a process called medialisation whereby the gap between the two vocal cords is closed and air leak is minimised; this results in a stronger voice.

Internal approach

Endolaryngeal approaches for glottic immobility were popularised in the 1960s by Arnold through the injection of Teflon directly into the immobile vocal fold. The use of Teflon over a period of time gave rise to a number of complications including stiffness and granuloma formation, often many years following the injection. This has led to the development of other injectable materials, with the common goal of finding a lasting bio-compatible material with viscoelastic properties similar to the superficial layer of the lamina propria, or that can be injected deep within the paraglottic space to medialise the vocal fold without long-term complications. Work is still in progress for the ‘perfect’ material.

I find (Bioplastique) Silicone – Polydimethylsiloxane gel mimics closely the properties of the superficial lamina propria and give predictable long term results. Medialisation of a paralysed right vocal fold is achieved with Bioplastique injection (Figs. 7–9).

Speech therapy and behavioural management

The behavioural approach consists of voice therapy which aims at restoring the best voice possible within the patient’s anatomical, physiological and psychological capacity.

A variety of techniques can be used in the treatment of voice disorders:

- Relaxation reduces musculoskeletal tension in the laryngeal area

- Breathing exercises optimise breath support for the voice.

- Various phonation exercises promote soft initiation of vocalisation, rather than hard glottal attack.

- Attention is paid to pitch, volume and rate of speech, to ensure that these are used appropriately.

- Voice therapy also aims to reduce stress factors that drive the individual into patterns of vocal misuse.

In non-organic voice disorders involving excess musculoskeletal tension, treatment is based on the principle that reduction in muscle tension allows the larynx to return to its normal phonatory ability. This is achieved by mechanical relaxation of musculature and psychological release of any anxiety causing or associated with the tension. Progression from abnormal to normal voice occurs as a product of the patient’s conscious, voluntary response to the clinician’s instruction and encouragement. In organic disorders, the main principle of therapy is either muscle strengthening or adaptation to the mechanical problems through compensatory phonatory and respiratory manoeuvres.

Conclusion

Voice disorders encompass a wide variety of conditions from different aetiological groups like infective, inflammatory, structural, traumatic, mass lesions - benign and malignant, neurological, endocrinal, vascular, autoimmune to name a few. The management involves a thorough understanding of the laryngeal function, diagnostic evaluation with attention to detail and a multidisciplinary team approach in treatment.

Acknowledgement

Mr Bhattacharyya acknowledges the input and help from Dr Ruth Epstein, PhD MRCSLT Head of Speech and Language Therapy at Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital.

For further information on the author of this article, Consultant ENT Surgeon, Mr Abir Bhattacharyya, please click here.

Associated with the nervous system and the brain.

Full medical glossary