Killer fungal infections causing 1.7M deaths a year

Prof Carlien Pohl-Albertyn (right) from the Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry at the University of the Free State is the NRF SARChI Research Chair in Pathogenic Yeasts. She and her team at the university are studying this neglected field, which annually claims the lives of 1.7 million people worldwide. It is estimated that over 3.2 million South Africans are afflicted by fungal diseases each year.

Prof Carlien Pohl-Albertyn (right) from the Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry at the University of the Free State is the NRF SARChI Research Chair in Pathogenic Yeasts. She and her team at the university are studying this neglected field, which annually claims the lives of 1.7 million people worldwide. It is estimated that over 3.2 million South Africans are afflicted by fungal diseases each year.

Prof Pohl-Albertyn explains that all these pathogenic yeasts are opportunistic pathogens, which cause disease when the immune system is under pressure.

The following people are at risk:

- those spening a long time in an intensive care unit;

- presence of a central venous catheter;

- a weakened immune system, for example, people on cancer chemotherapy, people who have had an organ transplant, and people with low white blood cell counts;

- recent surgery, especially multiple abdominal surgeries;

- recently received lots of antibiotics in hospital;

- receiving total parenteral nutrition (food through a vein);

- kidney failure or patients on haemodialysis;

- diabetes patients;

- pre-term babies;

- people who inject drugs.

What is the difference between baker's yeast and a killer fungus?

What is the difference between a pathogenic fungus or yeast that causes disease, and the harmless yeast we use to make sourdough?

What is the difference between a pathogenic fungus or yeast that causes disease, and the harmless yeast we use to make sourdough?

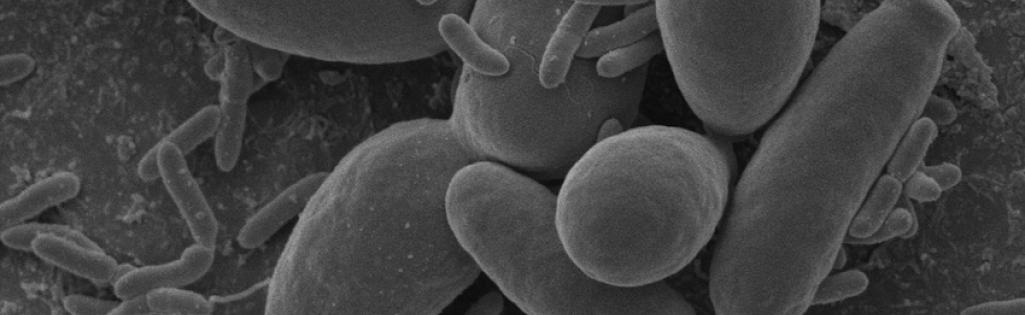

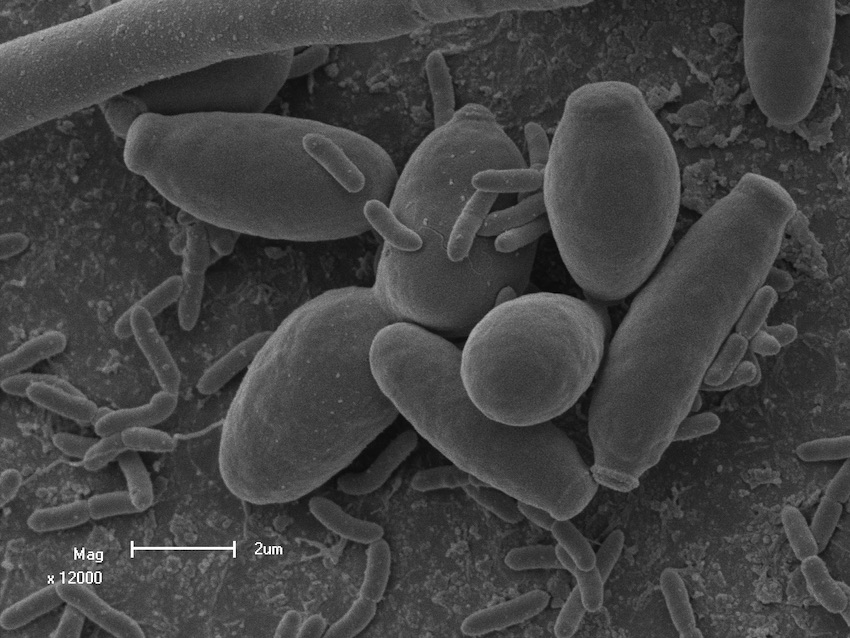

Pic; Yeast buddy or budding?

Fungi, except for mushrooms, are microscopic organisms and include yeasts, such as baker’s yeast. Yeasts are just unicellular fungi. The vast majority of fungi are not pathogenic (disease causing) and happily live all around us in the soil, on plants, in water, on food – becoming moulds when left too long. They even float around in the air that we breathe. We often use yeasts to prepare various foods such as bread, beer, wine, blue cheese, marmite, camembert and brie, coffee, chocolate, tofu, soy sauce and even to produce dugs such as penicillin.

The well-known fungus, Penicillium, was the original source of antibiotics. Fungi also make up part of our microbiome, which is all the micro-organisms that we carry on our skin, in our mouth, lungs, and in our gut. Under normal circumstances, these microbes do not cause any harm at all, and in fact, we cannot survive without them in - and as a totally natural part of our microbiome.

Good yeast gone bad

However, in someone who is immune-compromised in some way, or has a sugar imbalance can provide conditions for the fungus to become pathogenic (disease causing). A pathogenic fungus will break down the skin or mucosal cells in your body by secreting enzymes that can break down cell walls. The subsequent break-down products are used as food by the fungus. If the fungus gains access to the bloodstream, it is phagocytosed (swallowed) by 'hunter-killer' white blood cells. However, if the fungus can survive inside the white blood cells or is even able to break open the white blood cell, it can travel to any of your organs, where it will grow inside the organ.

Cryptococcal meningitis and the yeast capsule

Sometimes pathogenic yeasts are inhaled and can pass from the lungs into the bloodstream, where they are taken up by white blood cells. If they are not killed by the white blood cells, they can hide in these cells and infect different organs, such as the brain and kidneys. An example of a disease-causing yeast that infects the brain is Cryptococcus neoformans. It causes cryptococcal meningitis and death in 10-15% of HIV-positive patients. This yeast has a thick layer around it, called a capsule. The capsule protects the yeast against white blood cells.

The researchers are investigating the composition of the yeast capsule. They are trying to understand how certain molecules, including fatty acid metabolites in the capsule, help the yeast to protect itself.

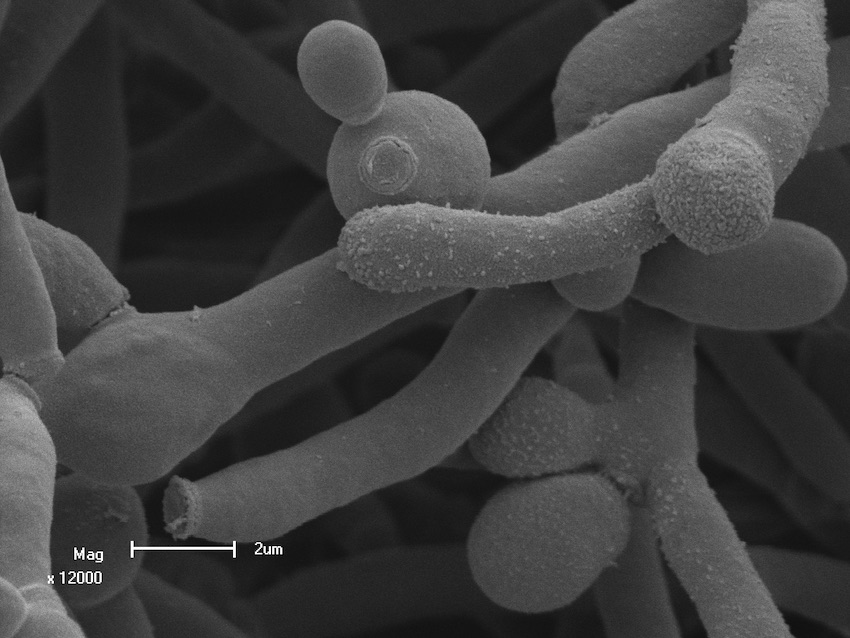

Invasive filaments

Other yeasts, such as Candida albicans, are part of the microbiome where they normally do not cause any problems, but when a person’s immune system is compromised, the yeast has the ability to form filaments that can penetrate between the human cells to reach the bloodstream. From there, this yeast can also infect many organs, including the lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, joints, and brain.

Common yeast species

The most common infectious Candida species is Candida albicans, and in South Africa it is followed closely by Candida parapsilosis and Candida glabrata. Other less common species are Candida tropicalis, Candida dubliniensis, Candida auris, and Candida krusei.

New yeast species from Japan

Candida auris is a new yeast species that was first identified 11 years ago in a hospital patient in Japan. Since then, it has spread to more than 30 countries, including South Africa, causing outbreaks in hospitals around the world. It is inherently resistant to fluconazole (a commonly used drug) and has also shown the ability to become resistant to the other classes of antifungal drugs available.

Prof Pohl-Albertyn says, “Very little is known about this yeast, but one theory is that it is an environmental yeast that may have been transferred to people via birds, and that climate change may have played a role in the emergence.”

Common yeast infections

Common yeast infections often affect the mucous membranes, such as vaginal infections (thrush) and oral infections, as well as skin infections, such as athlete's foot, jock itch, and ringworm. The symptoms of these superficial infections are irritation, itching, pain, redness. The symptoms of fungal bloodstream infections are often non-specific and include fever and chills. They are much more difficult to diagnose and require the culturing of a blood sample to detect the yeast or a biopsy to identify the specific organism.

Effective treatments for yeast infections are problematic

Treatment is highly problematic because there are only three types of antifungal drugs available. Some of the fungi are inherently resistant to the drugs. Furthermore, the really effective treatments also have nasty side effects. Finding effective treatments for fungal infections is a major challenge. In some respects, fungi are very similar to humans, so anything that damages fungal cells may also damage human cells.

In Prof Pohl-Albertyn’s laboratory, the team investigates various aspects of the functioning of the yeasts and fungi in order to find possible new treatments, as well as re-purposing drugs already approved for other conditions, which can be used in combination with antifungal drugs.

“We also study the role of fatty acids and their metabolites in the interaction between the yeasts and the host. These fatty acid metabolites are signals that can either cause or resolve inflammation in the host. They are produced by both the host and the yeast and are known to play an important role in host tissue damage, immune response, as well as enabling colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract by Candida albicans".

When yeast and bacteria join forces

When yeast and bacteria join forces

“Our lab also studies the interaction between Candida species and another opportunistic pathogens, the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The reason for this is that many infections are not caused by only one organism, but by both together – so we need to understand how they influence each other and how the combination influences the host,” she says.

Best gene editing technology

At the UFS, the team also uses the best gene editing technology in the world, called CRISPR.

“We use it in two ways: It can be used to delete genes in an organism. We can then compare the mutant strain with the original strain to see what the role of the specific gene is. We can also use it to add a fluorescent marker to a gene. The protein made by this gene will then fluoresce under a certain light wavelength and we can see where in the cell the protein is and also how much of the protein is being made by the cell. These techniques are all used to study the function of specific proteins related to the virulence and resistance in the yeasts.

However, biochemically speaking, fungi are very similar to humans, so anything that damages fungal cells may also damage human cells. "We are on the same branch of the tree of life, the Eukaryotes. This research takes grit, long-term endurance, and lots of funding".

A bacterium, virus, or other microorganism that can cause disease.

Full medical glossary