Bowel cancer, sometimes called colorectal cancer, is the second most common cause of cancer death. Senior Colorectal Surgeon Austin Obichere explains how to reduce risk through early screening, what is involved, and why early detection improves prognosis and outcome. It answers questions such as "Does inflammatory bowel disease increase the risk of cancer?" and "Should I be tested for bowel cancer?"

Contents

- The best approach to successfully treating bowel cancer

- Symptoms of bowel cancer

- What is screening and why should we screen for bowel cancer?

- What is the evidence that bowel cancer screening saves lives?

- NHS bowel cancer screening programme

- How can I take part in the NHS bowel cancer screening programme?

- Do I need to have a colonoscopy if I test positive for FOBT?

- Who else should consider a screening colonoscopy for bowel cancer?

- Summary

The best approach to successfully treating bowel cancer

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer deaths in the United Kingdom with 35,000 new cases and nearly 20,000 deaths per annum. The overall survival from this disease in the UK is about 45% and compares less favorably to 50 and 60% in France and Germany respectively. Some of the reasons for this disparity in survival are debatable and include previous poor funding from Government, the aggressive behaviour of some of the tumour types, late hospital attendance - when the disease has already spread and until more recently, the absence of a national bowel cancer screening programme.

Symptoms of bowel cancer

The presentation of bowel cancer may vary from no symptoms at all to worrisome complaints such as rectal bleeding, a change in bowel habit, weight loss and anaemia (low blood count). A low blood count in the absence of known common causes such as heavy periods or chronic ailments, warrants an examination of the entire gastrointestinal tract to exclude other pathology. Some patients with bowel cancer may notice an abdominal mass arising directly from the bowel wall, or indirectly due to blockage of the bowel and upstream distension. This abdominal swelling may be felt by the patient or their doctor.

What is screening and why should we screen for bowel cancer?

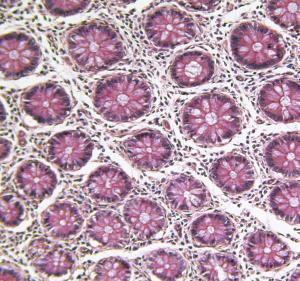

Some common health conditions may have an early form of the disease that can be prevented, diagnosed or treated with better outcome than if they were found much later when they may have already spread or become uncontrollable. Colorectal or bowel cancer is one such conditions that appear to have an early form or adenoma (benign growths of the lining of the bowel) that can be easily removed or destroyed at colonoscopy before they become malignant. Bowel cancer screening therefore provides a unique opportunity to prevent the disease developing and to improve prognosis by treating the pre-malignant or early stages of the condition.

What is the evidence that bowel cancer screening save lives?

There is good evidence from randomized clinical trials that screening for colorectal cancer using faecal occult blood (tests for hidden or occult blood in stool) saves lives, and equates to a 15-18% reduction in deaths in the group who underwent screening. For this reason and the success of the English Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot using postal faecal occult blood testing (PFOBT), the Department of Health formulated plans that led to the roll-out of the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme in the summer 2006. People aged 60-69 years who tested positive for PFOBT, were invited to undergo a colonoscopy at one of several National accredited screening centers.

NHS bowel cancer screening programme

The National Health Service bowel cancer screening programme was launched in an attempt to reduce the overall deaths from colorectal cancer by identifying the early stages of the disease that can either be prevented or cured surgically.

The programme which is currently being phased in over a 3 year period, targets both men and women between the ages 60-69 years. However, given the success of the programme so far, the Government has agreed to broaden it to include those between the ages 60 and 74 years, from April 2010. Once fully implemented, the country will consist of 5 regional Hubs who will be responsible for sending out kits, analyses of samples and despatch of results by post to patients. Each of the five Hubs will oversee up to 10 Screening Centres.

The screening centres will run regular Specialist Nurse clinics and are also charged with performing colonoscopy in patients who test positive. At the nurse clinics it is carefully explained that a positive test does not necessarily mean that one has bowel cancer, rather it indicates that there is blood in the stool and further examination of the bowel with a fibre optic camera (colonoscopy) is required. The colonoscopy examination is performed by experts who have been specially accredited by the National Joint Advisory Group for Endoscopy (JAG) to perform the procedure with little or no patient discomfort or complications. Those that are found to have bowel cancer are referred to a multidisciplinary colorectal cancer meeting at their local hospital where all experts who will be involved in their care, including the patient’s surgeon, discuss and agree on the best evidenced based treatment strategy.

How can I take part in the NHS bowel cancer screening programme?

At present, once your primary care trust within any of the 5 National Hubs has gone live with the programme, all males and females between the ages 60-69 years who are registered with a general practitioner will automatically receive a letter of invitation from their Hub Director. Those above 69 years of age can opt into the programme by contacting their Hub directly on a free phone number.

People within the programme are sent a bowel cancer screening kit which is self explanatory on how to use the kit in the privacy of your home and return the completed test in the enclosed addressed and stamped envelope that comes with the invitation pack. Each person within the screening age group is expected to receive an invitation to take part in the programme every 2 years.

Do I need to have a colonoscopy if I test positive for FOBT?

Currently, a colonoscopy examination is the gold standard not only to examine the bowel, but also enables tissue samples to be taken for diagnosis. Furthermore, precancerous growths from the bowel lining can also be removed at the same time. However, in some people with severe existing medical conditions who are deemed unfit and unlikely to tolerate a colonoscopy, a ct-pneumocolon (ct-colography or virtual colonoscopy) is an alternative. It is also not uncommon for some people to request these alternative tests even though they recognize a colonoscopy may still become necessary for the reasons outlined above.

Who else should consider a screening colonoscopy for bowel cancer?

Rectal bleeding: People with rectal bleeding or bowel symptoms for more than 6 weeks in line with the Department of Health guidelines for suspected colorectal cancer in primary care (Two Week Target Rule) should be referred to see a specialist unless an obvious cause has been found and treated successfully in the community.

Hereditary cancer: A strong family history of bowel cancer or those who are known to carry bad cancer genes such as FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis) and HNPCC (hereditary non- polyposis colorectal cancer) carry a near 100 percent risk of developing bowel cancer. These people should be referred to a specialist for advise on the timing and frequency of screening with the colonoscope.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease: People with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease for 10 years or more are at an increased risk of developing bowel cancer. This can occur where the disease is limited to the left side of the bowel, but is more common when both sides of the large bowel are affected. These patients require regular surveillance with a colonoscopy and tissue samples are taken to detect any abnormal changes in the bowel lining.

Previous history of bowel cancer: Patients who have been treated for colorectal cancer require intensive follow- up with regular colonoscopy every 3-5 years or sooner should they develop new symptoms. Screening colonoscopy is discontinued in the elderly or those with serious medical conditions where the risks of colonoscopy outweigh the potential benefits of screening.

Summary

Colorectal cancer is a major cause of cancer deaths in the UK and improved surgical outcome or cure is dependent upon diagnosis and treatment of early stage disease. Bowel cancer screening detects early disease and saves lives.