Skin Cancer - Contents

Who is at risk of skin cancer and why?

How is sunlight harmful to skin?

What signs of skin cancer should I watch out for?

What treatments are available for skin cancer?

Photodynamic therapy for skin cancer

Novel treatments for skin melanoma

How common is skin cancer?

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer both in the UK and worldwide, with 1 in 3 cancers being in the skin and 1 in 5 people developing skin cancer at some point in their lives. The most common types in order of decreasing frequency but increasing severity are basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. The incidence rates of skin cancer overall are increasing year on year with data from 2010 revealling over 112,000 cases of skin cancer in the UK.

Who is at risk of skin cancer and why?

Individuals most at risk have fair complexions, are unable to tan and may have a family history of skin cancer. However as we all should know, it is exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) which is the biggest environmental factor. UVR comprises 3 different rays - UVA, UVB and UVC. There are many reasons for why there has been increased exposure to UVR in recent decades including the trend to travel to sunny climates, the fashion to appear tanned and the use of sunbeds. Furthermore depletion of the ozone layer allows more penetration of UVR into the atmosphere.

Although proponents of the tanning industry suggest that sunbeds help stimulate vitamin D production, most tanning devices primarily emit ultraviolet A which is relatively ineffective in stimulating vitamin D. Therefore the risks outweigh the benefits.

How is sunlight harmful to skin?

Melanocytes are the pigment producing cells in the skin, hair and eyes that determine their colour. When skin is exposed to the sun’s UV rays melanocytes produce more pigment causing the skin to tan, which is the body’s way of protecting itself. However over exposure means the skin cannot protect itself adequately and the DNA within the cells becomes damaged. This leads to cancerous cells which then multiply. People with less natural pigment will have less protection.

What signs of skin cancer should I watch out for?

Most commonly people are advised to watch out for changes in moles or for new moles. The ABCD guide is helpful and stands for:

Asymmetry

Border becoming irregular

Colour changes especially uneven colour

Diameter of greater than 6mm

It is important to note however that melanoma tends to appear as a new lesion more often than developing from a pre-existing mole. Therefore, a new mole or one which is out of keeping with the surrounding moles should be scrutinised more carefully. Moles which become itchy or bleed may also need further specialist attention.

It is also important to realise that most skin cancers do not appear as “moles” in the typical sense. Basal cell carcinoma may appear as a pearly pink/red nodule, a red scaly patch or an ulcer. There is often a history of bleeding. Squamous cell carcinoma often appears as a scaly or crusty area of skin or lump, with a red, inflamed base. They may be tender and bleed when rubbed.

Also, as we age we develop scaly rough patches predominantly in sun exposed areas (e.g. face, ears, scalp in balding areas, backs of hands and forearms). These are known as actinic keratoses and they become more common with advancing age especially in fair skinned people with a history of sun exposure. These occasionally develop into squamous cell carcinoma and so can be considered pre-cancerous.

Images of typical actinic keratoses

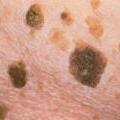

Fortunately most skin lesions are harmless and we are more likely to develop benign lesions as we get older. Seborrhoeic keratoses are good examples of such skin growths. These are not related to actinic keratoses above but can be confused with them. They can mimic skin cancer and so not infrequently are a cause of concern.

Images of typical seborrhoeic keratoses

It can be difficult for an untrained eye to tell the difference and so if you are concerned it is best to seek your GP’s opinion and if necessary refer to a dermatologist. If in doubt get it checked out!

What treatments are available for skin cancer?

Fortunately most skin cancers can be effectively cured with early detection and appropriate removal. The exact treatment depends on the type of lesion and so an accurate diagnosis is critical. This may require a skin biopsy of the lesion in question.

For superficial skin cancers such as superficial basal carcinoma or pre-cancerous lesions such as actinic keratoses, non-surgical treatments including creams may suffice.These are applied daily for several weeks and cause an inflammatory reaction where they are targeting the tumour cells. This can be quite alarming particularly on the face but shows that the skin is attacking the abnormal cells.

Photodynamic therapy for skin cancer

Another interesting treatment for superficial cancers is photodynamic therapy. A special cream is applied onto the affected area and then covered with a dressing. After 3 hours the dressing is removed and a specific light is shone on to the area for around 9 minutes although this will depend on the exact protocol. A chemical reaction preferentially destroys the abnormal cells rather than the normal skin. The treatment is usually repeated twice one week apart to optimise the chance of success for superficial basal cell carcinoma. There is some discomfort during the treatment due to heat from the reaction although the skin can be cooled with the use of a cold air machine. Over the subsequent few days the treated area may crust but the advantage is that there is usually rapid healing with an excellent cosmetic outcome.

Surgical removal of skin cancer

For more advanced skin cancers treatment is usually by surgical removal (excision). The standard method is to remove the cancer and a pre-determined margin of normal skin. This is because there are often tumour cells that cannot be detected with the naked eye and this increases the chances of complete removal. The removed skin is then sent to the pathology laboratory for testing. For melanoma, early surgical removal remains the most effective treatment. The outcome will depend on a variety of factors including pathological features such as the thickness of the tumour and whether it has spread to lymph nodes.

Mohs micrographic surgery

For certain higher risk tumours, for example on the central face and ears, Mohs micrographic surgery can be advantageous. This is a very precise method of tumour removal, which involves taking narrow margins of normal skin, mapping the tissue and processing it rapidly in a nearby laboratory while you wait. The skin is processed in a special way with horizontal sections so that the entire margin is examined rather than only a small proportion as with the standard processing discussed above. Results are often available within 1 hour and the slides are then read by the Mohs surgeon who then pin-points where further skin removal is required. This can reduce the risk of scarring or disfigurement by preserving normal tissue. Furthermore, by tracing out all of the tumour roots microscopically, the chance of leaving tumour behind is decreased. For this reason with appropriate tumours (most commonly basal cell carcinoma) Mohs surgery has a 99% cure rate.

Radiotherapy treatment for skin cancer

Radiotherapy is an option where surgery is not deemed appropriate. Radiation is directed to the tumour and destroys the cancer cells by damaging the DNA inside. However radiation cannot distinguish between normal cells and cancer cells and so both are affected. It relies on the fact that normal cells are more likely to recover from the damage making the treatment relatively selective for the tumour. It is important to be aware that multiple visits to the hospital are necessary and the total treatment course can take at least 3 weeks to complete.

Novel treatments for melanoma

Unfortunately, there is still no cure once a melanoma has spread (metastasised) beyond the skin, however on-going research continues to search for novel treatments. This includes molecules which block the mutations causing abnormal growth of cancer cells, vaccine therapy to stimulate the body’s immune system to recognise and attack melanoma cells, gene therapy, which aims to replace the damaged genes in melanoma cells with normal ones and antibodies to attack the tumour cells. In the future treatment may be tailored to an individual cancer “gene signature” based on gene expression analysis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the rise in skin cancer shows no sign of abating. The presentation varies tremendously and there are many different types of skin cancer. The treatment will depend on the tumour type, location on the body and various other factors, which determine the aggressiveness of the cancer. Therapies may range from the application of creams to more complex surgery. However, there is no doubt that the right treatment approach can only start with an accurate clinical diagnosis.

Useful links:

www.macmillan.org.uk/Cancerinformation/Cancertypes/Skin/Skincancer.aspx